Some Important Questions

But, liberalization has provided opportunities as well. Have Dalits been able to take advantage of the improved climate for business by starting their own enterprises? Or, does caste come in the way of entrepreneurship too? After all, capital, skills and education are all important ingredients for entrepreneurship, so it is reasonable to expect that restricted access to these ingredients might impede entrepreneurship.

When I heard that there is a new book on Dalit entrepreneurship, I was keen to read it in the hope that it would answer some of these questions as well as give us a picture of what is coming in the way of entrepreneurship by people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The Book

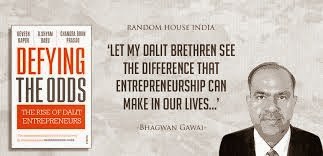

Defying the Odds: The Rise of Dalit Entrepreneurs (Random House India, 2014) by Devesh Kapur, D. Shyam Babu and Chandra Bhan Prasad is a must read for anyone with an interest in the present and future of Indian society. I read it carefully the first time, and went through it a second time to take notes. [The picture below shows Devesh Kapur, one of the authors.]

This book tells the stories of 21 successful dalit entrepreneurs spanning the north, west and south of India. I don’t know why the east is left out, but that’s possibly because the headquarters of the main dalit industry association (DICCI) is in the west, in Pune.

Broad Patterns

Most of these dalit entrepreneurs have come from large families with several siblings. Almost without an exception, their parents recognized the importance of education, but lacking the resources to educate all their children, focused on one or two. These dalit entrepreneurs were largely part of these chosen few.

None of these dalit entrepreneurs have had it easy. Most started from extreme poverty. Loss of one or more parent early in life was common. They have gone through cycles of their own, almost losing all their resources and then starting again. Their success is due to their perseverance, their ability to pick themselves up and go forward again.

[The picture below shows one of the protagonists - Milind Kamble - with one of the authors - Chandra Bhan Prasad.]

Though many of them were born in rural locales, most of them succeeded as entrepreneurs in urban centres. Mumbai, Nagpur, Pune, Jaipur, Noida, Delhi, Lucknow and Hyderabad are some of the places where their enterprises succeeded. This only reinforces BR Ambedkar’s memorable comment: “What is a village but a sink of localism, a den of narrow-mindedness, and communalism?” Cities offer not only the advantages of agglomeration and specialization, but also the benefits of relative anonymity.

Though dalit entrepreneurship may be seen as an alternative to government employment, that’s probably too simplistic. A government job, particularly as an officer, comes through from many of the life stories, as a preferred mode of enhancing one’s status and economic condition. Though there are only three cases reported in this book where someone left a government or public sector job to start an enterprise, reservation plays an indirect role in many of the stories – a brother or spouse has a government job that provides economic stability; reservation in academia provides access to a diploma or degree either to the protagonist or a sibling; or the elusive quest for the civil services acts as a spur for higher educational qualifications even though the quest is ultimately unsuccessful.

No person becomes successful on his own, and none of these 21 entrepreneurs (20 male and one female) were an exception to this. While the unsurprising sources of support are family (father, mother, wife, husband, brother, sister), it was refreshing to read about many higher caste men who supported them with capital, shelter or mentorship. Many of the successful entrepreneurs in this book had non-dalit partners at some time or the other.

The most impactful non-dalit supporter was a school teacher who inspired one of the entrepreneurs, Murali Mohan, when he was young. Not only did he prevent Murali Mohan from dropping out of school by providing accommodation at his home, he persuaded Murali’s father to educate him in Bangalore and insisted that he pursue science. With an MSc in Biotechnology and a diploma from the Central Food Technology Research Institute in Mysore, Murali an exporter of gherkins, is one of the best educated in this group of entrepreneurs.

Though several women feature in this book by either educating their children or supporting their husbands, only one woman dalit entrepreneur is profiled. I guess one should not be surprised that it’s difficult to overcome the twin disabilities of caste and gender.

Sectoral Coverage

The range of industries represented by the entrepreneurs in this book is wide. Dealing in scrap, hospitals, garment exports, oil trading, pest control, repairing oil rigs, polymer trading, cable laying, gherkin exports, logistics, packaged foods and steel rolling are some of the businesses started by these entrepreneurs. Real estate and construction figure in multiple stories, and seem to be an important means of wealth creation.

The overall trend towards outsourcing has opened up opportunities for many of these entrepreneurs, allowing them to be either the one providing the outsourced service, or using outsourcing as a means of lowering the capital required to enter a business. I thought that modern technology industries such as software and BPO should be relatively free of caste biases and was hence surprised to find no story from these industries in this book. Of course, that may just be an artifact of the sample the authors had access to (largely from the DICCI database, it appears).

The formal financial system – banks, other finance companies, private equity, etc. – is conspicuous by its absence from this book. This may be because the book is focused more on the entrepreneurs than their financing strategies, but I find it strange that these financial institutions don’t figure at all. This certainly merits further investigation.

A Policy Takeaway

For me, the biggest policy takeaway from this book is the importance of education. If only the parents of the entrepreneurs profiled here could have educated more of their children, we might see more entrepreneurs. This book demonstrates that entrepreneurial drive has nothing to do with caste, and we are missing out on creating many more successful entrepreneurs if we don’t provide an easily accessible basic education to all.

——-

Rishikesha Krishnan

(The author is the Director of IIM Indore. Previously, he was the Professor of Corporate Strategy at IIM Bangalore. He received the Thinkers50 innovation award last year. He is the writer of ‘From Jugaad to Systematic Innovation: The Challenge for India‘ and co-author of ‘8 Steps to Innovation‘. He blogs on http://jugaadtoinnovation.

We are privileged to begin a new weekly column titled ’Jugaad to Innovation’ by Prof. Rishikesha Krishnan, Director – IIM Indore.

(This work was originally published here)

Comments